Best Med #2: GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

Next up: glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, known colloquially (and identified here) as GLPs.

These drugs mimic a class of hormones called incretins, which enhance the release of insulin in response to ingestion of glucose—the so-called “incretin effect.” Originally identified in 1987, glucagon-like peptide 1 is a natural protein produced by the body. It not only enhances insulin production and release, but also decreases glucagon secretion, increases glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis in peripheral tissues, delays gastric emptying, and increases satiety. Since this discovery, GLP-1 receptors have been identified in a number of tissues, including the GI tract, pancreas, brain, lung, and kidney. To date, their roles are not entirely understood across all organ systems.

GLPs are synthetic analogues of naturally occurring GLP hormones that stimulate GLP-1 receptors. The GLPs share the same underlying mechanism of action, but they differ in terms of formulations, administration, injection devices and dosages.

SOURCE: Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Smith BA. GLP-1 receptor agonists: an updated review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021.

Given their ability to increase insulin release and enhance insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, these drugs were identified as, and remain a key therapy for type 2 diabetes. All of the known GLPs produce clinically significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels.

SOURCE: Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Smith BA. GLP-1 receptor agonists: an updated review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021.

And as compared to older diabetes medications like insulin and sulfonylureas, GLPs carry a low risk of hypoglycemia.

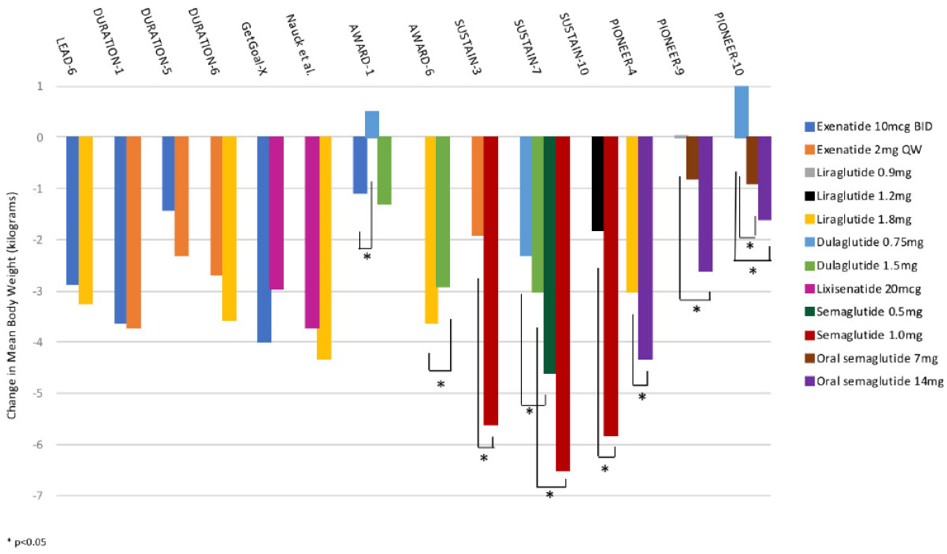

Higher dose GLP therapy has also demonstrated another important metabolic benefit—weight loss!

SOURCE: Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Smith BA. GLP-1 receptor agonists: an updated review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021.

These agents delay gastric emptying which makes patients feel fuller for longer. In addition, it seems that they also act on appetite centers in the brain and gut to enhance satiety. Many of the patients from my medical weight management clinic who start on these agents express amazement and gratitude that they no longer think as much about food.

Until recently, only liraglutide was FDA-approved for weight-loss in non-diabetic patients under the trade name Saxenda. This approval came after the SCALE Trial showed that high dose liraglutide not only better prevented progression from prediabetes to diabetes (as compared to placebo), but also had a threefold impact on weight loss. When combined with diet and exercise, liraglutide can be an important piece of a comprehensive treatment plan for weight loss maintenance.

More recently, trials have explored the potential of semaglutide, a more potent cousin of liraglutide, to promote weight loss. The STEP trials are testing semaglutide at the higher dose of 2.4 mg/week (as compared to 1.0 mg/week for the original diabetes indication), specifically for promoting weight loss, regardless of the presence of type 2 diabetes. In STEP 1, in a population of obese or overweight people without diabetes, those who received semaglutide 2.4 mg plus a lifestyle intervention over 68 weeks lost an average of 14.9% in bodyweight as compared with just a 2.4% reduction in the placebo plus lifestyle intervention group. And in the STEP 3 trial, participants who received semaglutide 2.4 mg plus intensive behavioral therapy lost an average of 16.0% of their bodyweight (as compared to 5.7% in the placebo group). Given these impressive findings, semaglutide has been hailed as a “game changer” in the treatment of overweight and obesity. Appropriately, and in the midst of writing this article, the FDA approved semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly for weight loss alone, specifically for adults with BMI of 27 mg/m2 with one or more weight-related comorbidities or in adults with a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2.

As opposed to some other diabetes and weight management medications, GLPs are particularly beneficial in patients with atherosclerosis, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease. Seven cardiovascular outcomes trials have been performed in the past 4 years, all of which found non-inferiority for cardiovascular outcomes, with many finding superiority of these drugs. Randomized controlled trials with liraglutide, semaglutide, albiglutide, and dulaglutide have shown significant reductions in composite cardiovascular outcomes. Professional society guidelines now recommend GLP therapy for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiac risk factors. Many of these same trials also found favorable impact on kidney health. Given the prevalence of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and metabolic syndrome, it seems plausible that GLP1’s reduce all-cause mortality.

As a class, the GLPs are generally well tolerated. The most common adverse events are nausea and vomiting, both of which are usually transient and of mild severity. The majority of these medications are currently administered through an injectable pen. Oral formulations continue to be developed, which may reduce some barriers to use. Currently, the biggest barrier to adoption is insurance coverage for these medications which have a prohibitive out-of-pocket cost. And GLPs are not recommended in patient populations with: severe gastrointestinal diseases such as gastroparesis and inflammatory bowel disease; a personal or family history significant for multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A, multiple endocrine neoplasia 2B, or medullary thyroid cancer; or a history of pancreatitis.

I am bullish on GLPs and prescribe them as often as possible for weight management. These analogues of natural hormones stimulate the satiety pathway and improve the physiological response to food, which often gets dysregulated in obesity. These agents are a much safer and sustainable option than amphetamine-based appetite suppressants like phentermine which come with negative side effects, questionable long-term safety, and rapid acclimation. Given the continued growth of the obesity epidemic, primary care providers should prescribing GLPs for patients with nondiabetic obesity. Of course, pharmacotherapy is not the sole solution for weight loss. While it can be a key component of a comprehensive weight loss plan, lifestyle change remains the foundation of sustainable weight loss.

At this time, there are no studies assessing the effect of GLP’s for general health promotion and longevity in non-obese adults. As is generally true for the complex biochemistry of our bodies, too much of any one thing can turn detrimental. Insulin is an anabolic hormone that stimulates a number of cellular responses, which can wreak havoc on bodily functions if unconstrained. (More to come on this at a later date). For now, and in the context of GLP therapy, it will be important to first better understand the insulin release and response kinetics in normal weight, nondiabetic patients before recommending these meds for a broader population.